When I asked my friend Martin to write about the horror movies that made him, he touched on a critical component: score. While I respectfully disagree that Halloween would be pedestrian without its soundtrack, there’s no way of knowing and I don’t even want to imagine my life without Carpenter’s keyboard. Score matters. Psycho, Friday the 13th, Jaws (if you consider that horror). Personally, nothing strikes fear in my heart like Mike Oldham’s Tubular Bells from The Exorcist or Gobin’s iconic scores for Dario Argento, in particular Suspiria. There’s something about the simple use of keys and strings that seem made for horror.

Sometimes score is simply soundscape. Four words here: Texas Chain Saw Massacre. Following John Larroquette’s monologue and the very first image of two still-meaty skeletons lashed to a graveyard monument, Wayne Bell raises TCSM‘s ambient terror to a fever pitch just a few minutes into the film. His admixture of sound intensifies as the screen turns to a swirling red and black that, for me, has always foreshadowed the malevolent planetary forces that Pam reads about in her American Astrology magazine. For more detail on Wayne Bell’s sound design for TCSM, click here.

Sometimes, it’s a film’s use – and inherent transformation – of songs we know and love. I can’t hear Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried” or The Fixx’s “One Thing Leads to Another” without thinking of The Strangers and The House of the Devil, the latter a surprise Joe Bob Season One selection.

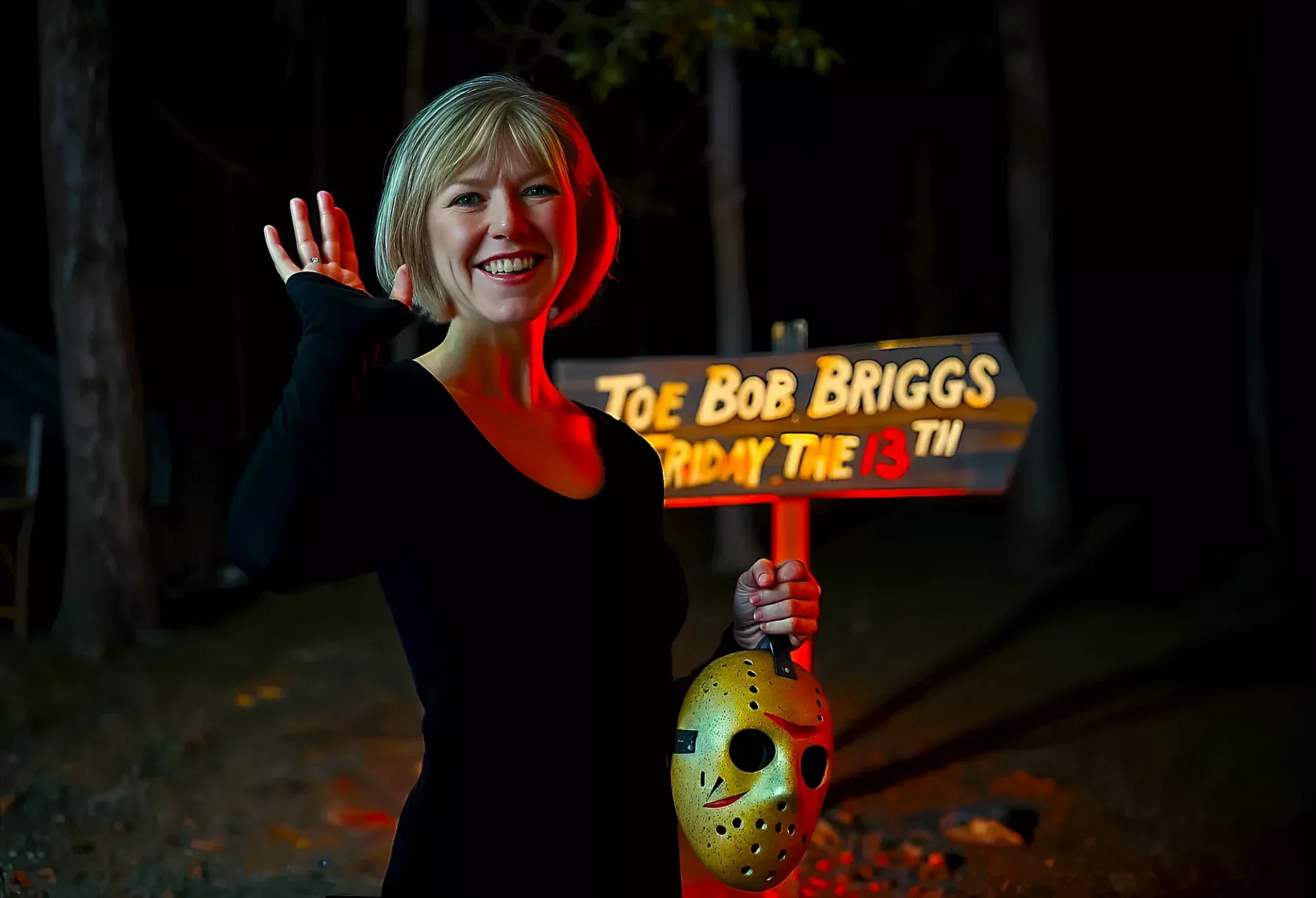

Of course, horror scores don’t have to be scary. Think John Brennan’s brilliant theme for The Last Drive-In or the folk songs from The Legend of Boggy Creek. They both set the mood and help us settle in – with the help of a case or three of Lone Star.

Sometimes a score is unintentionally funny – at least to our 21st century “woke” ears. When it comes to horror and thrillers, I love Italian anything. But more often than not when listening to the scores of Italian gems from the 60s and 70s, I’m not sure whether I’m watching a spaghetti Western, spaghetti slasher or comedy-sex romp. Sergio Martino’s All the Colors of the Dark – scored by Bruno Nicolai – is one example.

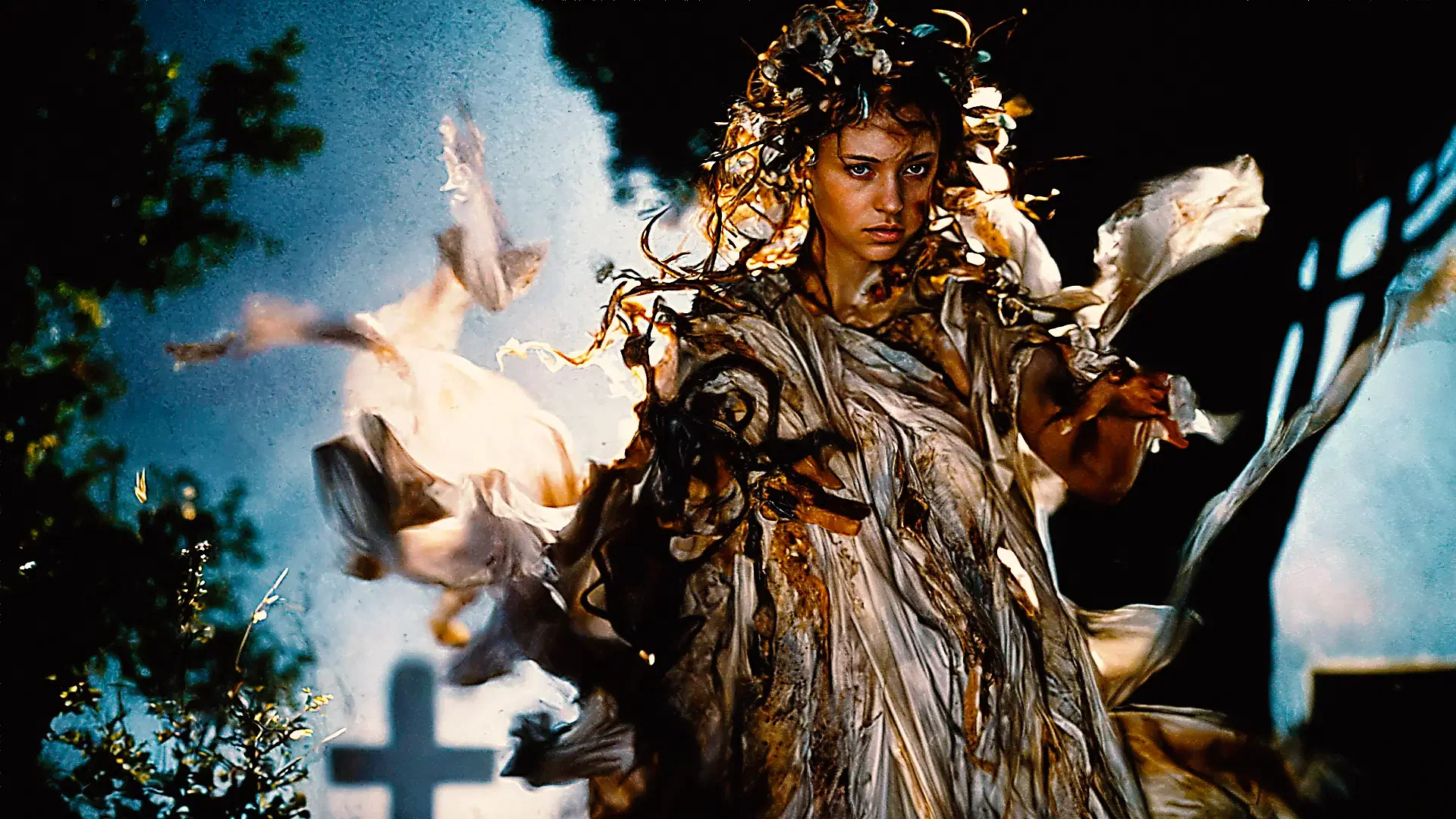

Nicolai’s score represents a specific place in time. The use of genre music in horror – pop, metal, jazz – can also create such time stamps. After years of giving us Goblin’s synthesizers, Dario Argento mixed it up with 1985’s Phenomena which – after a dreamy opening score – switches to full-on metal with Iron Maiden and Motorhead. Friend of the blog and The Last Drive-In Pete Soards (@endosepsis), shared with me his love of Lamberto Bava’s Demons‘ and the industrial-metal feel of its title score (also by Goblin). Pete’s other musical faves include Danny Elfman’s Army of Darkness, Dollman vs. Demonic Toys, and Re-Animator‘s main title theme – an inverse of the Psycho score according to the DVD commentary. Thanks Pete for the contributions and the info!

Before we go, you didn’t think I’d forgotten The Shining did you? For me, it triggers a long-standing question I have about modern composers and their use of classical compositions to create movie scores. No disrespect to the amazing Wendy Carlos. It’s hard to imagine Stanley Kubrick’s sweeping, distorted opening without her haunting adaptation of Hector Berlioz’s Dies Irae.

Sometimes composers even borrow from themselves. it’s always fun to hear just a few notes and connect one film to another through a common artist. I recently rewatched Vertigo. In addition to being stunned by the film’s dread and power, I had to pause its amazing title credits to dig into why the score reminded me so much of Cape Fear – because they had the same composer, the incomparable Bernard Herrmann whose collaborations with Hitchcock produced some of the finest music in cinematic history.

What are your horror music favorites? Let us know and tune in next week for the latest installment of LAST CALL Film School!